Introduction

Hi! My name is Sreekar Baddepudi and I was a high school intern this summer at the UCSF NeuroAI Lab through the Radiology Initiative for Scholarly Engagement (RISE Program). I had the opportunity to work on the exploration of generative AI technology in the Memory and Aging Center.

My main project focused on using multimodal AI to predict subtypes of Primary Progressive Aphasia (PPA) by combining clinical notes and MRI scans. Alongside that, I also helped test the Memory and Aging Center’s new vCDR tool and explored other ways generative AI could be useful in both research and clinical care.

Summer Research Overview

What is PPA?

Primary Progressive Aphasia (PPA) is a neurodegenerative syndrome characterized by progressive breakdown of language abilities (Gorno-Tenpini et al., 2011). It is associated with atrophy of the frontal and/or temporal lobes (Mesulam et al., 2014) and can be pathologically based in underlying Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) (Harris et al., 2013).

PPA is usually divided into three main variants:

- Nonfluent variant (nfvPPA): speech becomes effortful and grammatically broken (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2011)

- Logopenic variant (lvPPA): frequent word-finding pauses (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2008)

- Semantic variant (svPPA): loss of word meaning (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2011)

What does current PPA diagnosis look like?

Contemporary diagnosis of PPA is heavily dependent on the work of a skilled, multidisciplinary team across neuropsychology, neurology, and radiology (Roytman et al., 2022; Ortiz et al., 2025). On the machine learning side, current methods for classifying PPA tend to treat MRI and clinical data separately (Warner et al., 2024). But language and brain imaging complement each other (Cotelli et al., 2023). That’s where multimodal models come in. Newer AI architectures, like OpenAI’s CLIP, are trained to align different types of data through zero-shot training (Warner et al., 2024). In the case of CLIP, it was designed to create captions for images by aligning text with 2-D images (Radford, Sutskever, Kim, Krueger, & Agarwal, 2021).

How can we apply this to PPA?

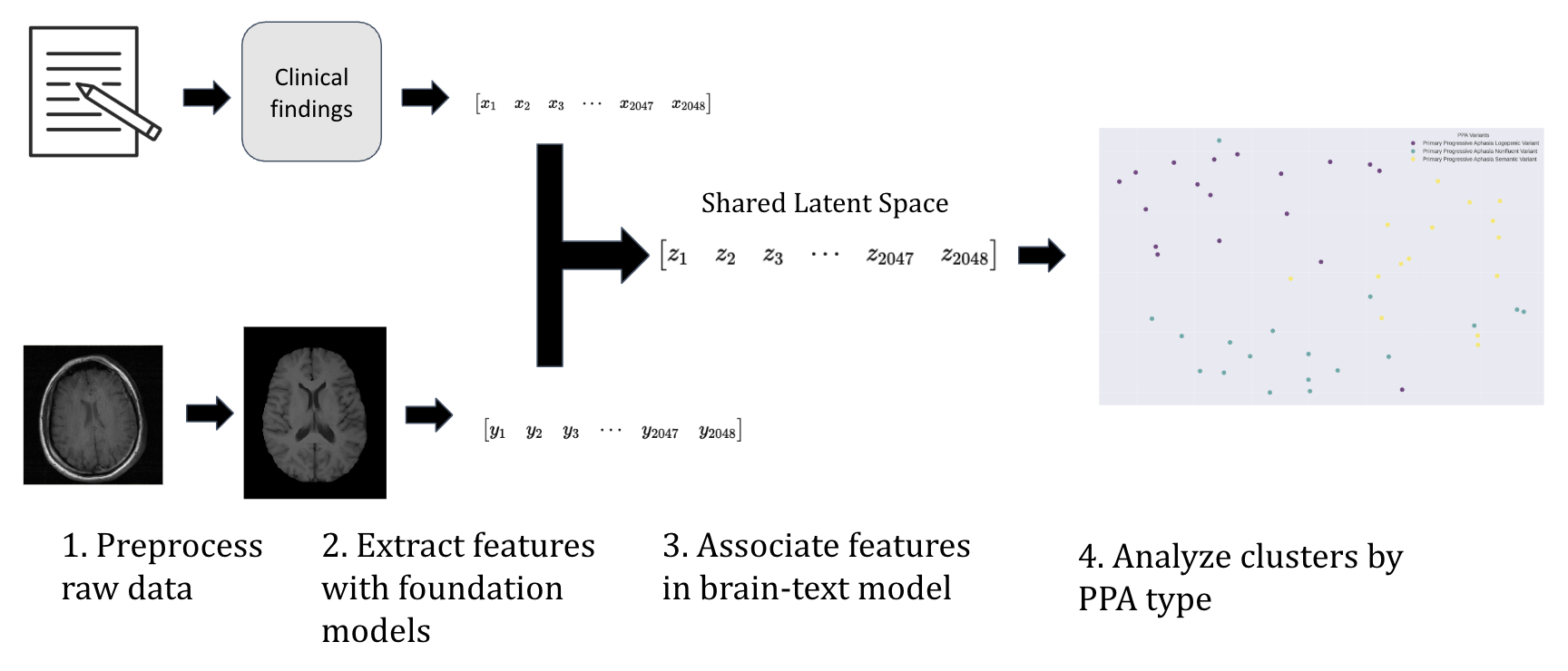

In this experiment, the hypothesis was that by combining clinical notes with MRI imaging in a multimodal model, we can improve diagnostic accuracy across patients with well-characterized PPA variants. The overall aim is for this framework to be able to classify PPA variants through joint embeddings of both text and MRI.

For the first modality, we focused on clinical notes. These are often the richest source of information about a patient’s symptoms (Koleck et al., 2021; Dubois et al., 2017). Clinical findings of interest were extracted, focusing on features like word-finding pauses, comprehension difficulties, etc., depending on the patient’s variant. To transform these unstructured clinical narratives into machine-learning-ready representations, we employed OpenAI’s Embedding 3 Large model (OpenAI, 2024). This approach converts natural language descriptions into high-dimensional numerical embeddings, providing a structured way to capture clinical data’s complexity (Lho et al., 2025).

The second modality consisted of structural brain imaging data from T1-weighted MRI scans, which reveal the characteristic patterns of atrophy that distinguish PPA variants (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2011). All MRI scans were preprocessed through the BrainIAC pipeline, which standardizes images by aligning them, removing artifacts, and normalizing intensity values. This ensures that all scans are comparable across patients and ready for the BrainIAC model. For feature extraction, we used the Kann Lab BrainIAC foundational model. This model was trained on more than 50,000 brain images, giving it strong domain knowledge of brain MRIs specifically (Tak et al., 2024). This model was not further trained for this project. The result is a set of embeddings for MRI scans, much like the text embeddings, but now capturing the structure of each patient’s brain (Tak et al., 2024).

We used a CLIP-inspired architecture (Radford, Sutskever, Kim, Krueger, & Agarwal, 2021) to pull text and MRI embeddings into a shared latent space. This allowed the model to “learn” cross-modality associations. This clip architecture learns through a method called contrastive loss. In simple terms, contrastive loss teaches the model by showing it pairs of data and asking if they belong together or are mismatched.

The model is rewarded when it pulls true pairs closer together in the shared space, and pushes mismatched pairs further apart, learning the relationships across modalities. As a result, the model can cluster patients based on both their clinical presentation and brain structure.

An important thing to note is that both the embedding models were foundational models meaning that there was no fine-tuning for increased performance in the domain of PPA.

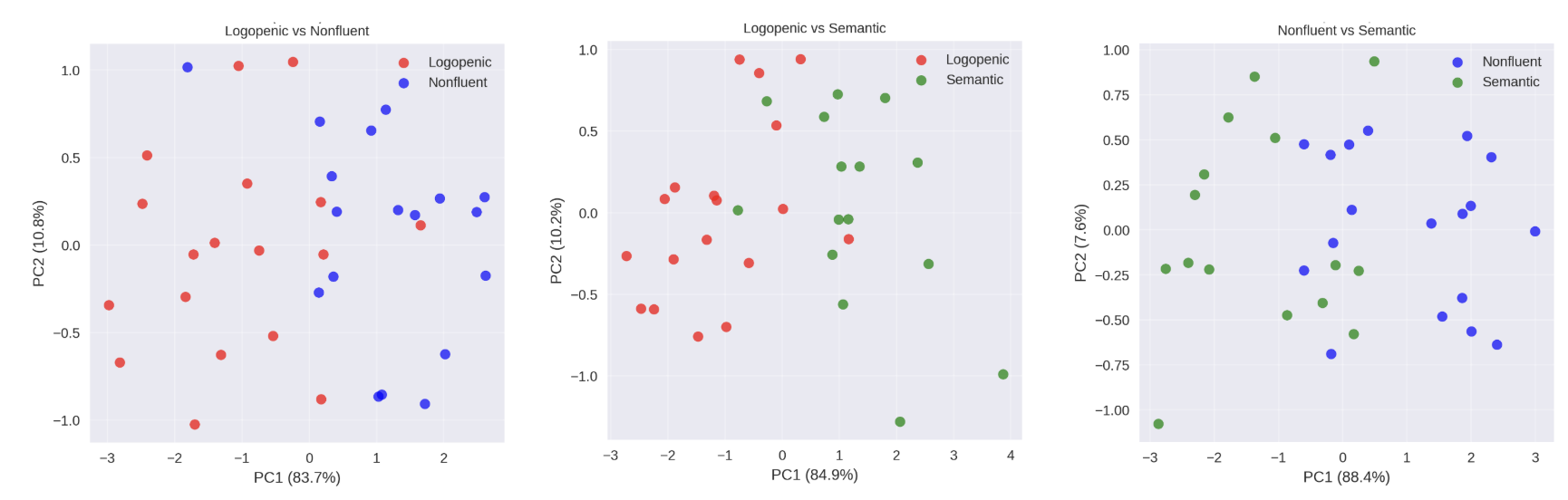

What were the results?

When we tested our multimodal model, we compared the three modalities: MRI alone, clinical notes alone, and a combined CLIP-inspired approach. The metric we are using to measure how well a model can distinguish between two classes is AUC, which stands for Area Under the Curve. An AUC of 0.5 means the model is no better than random chance, while an AUC of 1.0 indicates perfect separation.

- Subtype Discrimination

The multimodal model showed strong ability to distinguish between different PPA variants:

- Logopenic vs. Nonfluent: AUC = 0.842

- Logopenic vs. Semantic: AUC = 0.833

- Nonfluent vs. Semantic: AUC = 0.750

In plain terms, the model was very good at telling apart logopenic and nonfluent cases, and logopenic and semantic cases. Distinguishing between nonfluent and semantic was a bit harder, which makes sense clinically, since these subtypes often show overlapping features.

- Performance by Modality

- MRI only: AUC = 0.741

- Clinical notes only: AUC = 0.722

- CLIP multimodal (text + MRI): AUC = 0.808

The combined model outperformed either modality on its own. This shows the value of integration: clinical notes capture what the patient experiences, while MRIs capture what’s happening in the brain. Together, they tell a more complete story.

| Method | Logopenic vs Semantic | Logopenic vs Nonfluent | Semantic vs Nonfluent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Concatenation | 0.578 ± 0.121 | 0.717 ± 0.201 | 0.872 ± 0.094 |

| Weighted Avg (Clinical 70%) | 0.600 ± 0.138 | 0.817 ± 0.186 | 0.900 ± 0.089 |

| Weighted Avg (MRI 70%) | 0.656 ± 0.181 | 0.583 ± 0.105 | 0.900 ± 0.089 |

| CLIP | 0.833 ± 0.175 | 0.842 ± 0.140 | 0.750 ± 0.134 |

| MRI Only | 0.789 ± 0.124 | 0.750 ± 0.139 | 0.683 ± 0.131 |

| Clinical Only | 0.578 ± 0.121 | 0.717 ± 0.201 | 0.872 ± 0.094 |

CLIP and weighted fusion methods outperform simple concatenation, showing better integration of text and MRI data. MRI-only models remain strong, while clinical-only and simple concatenation fusion perform weakest.

Conclusion

This project showed that multimodal AI can make a real difference in understanding complex brain disorders like PPA. By combining clinical notes with MRI scans in a shared latent space, we were able to capture more subtype-relevant information than when using either modality alone. The CLIP-inspired model, trained with contrastive loss, discovered meaningful clusters that reflect both language symptoms and brain atrophy patterns.

What does the future hold?

Looking ahead, there are several options. I would love to explore different embedding methods and incorporate additional data modalities, ideally with larger sample sizes. This project served as a great way to gain a deeper understanding of multimodal learning techniques, so moving forward I would love to develop a more domain specific architecture for PPA, possibly through a custom transformer rather than foundational models.

This is an exciting step toward diagnostic tools. For patients, this could mean clearer diagnoses, more personalized care, and earlier interventions. For researchers, it opens the door to discovering new phenotypic boundaries that haven’t been defined clinically.

My Internship Experience

Interning at the UCSF NeuroAI Lab granted me a portal into the inner workings of the intersection of technology and medicine that is revolutionizing approaches to neuroscience. From lab meetings to individual interactions, the ability to have a window into how AI is interacting with neuroscience at both a clinical and research level was extremely powerful.

In addition to my main project on multimodal PPA classification, I also worked on a large language model–powered PubMed citation generator to streamline literature review and an atrophy predictor from clinical notes, which explored how much we can infer about brain changes just from a patient’s written record.

Being on site was one of the most rewarding aspects of the internship. I had the chance to interact with experts across disciplines and even shadow clinicians during real patient visits. One of the most fascinating experiences was the Clinical Pathology Conference, where members of the Memory and Aging Center walked through the full progression of patient diagnosis and treatment from initial meeting to pathology. One of the coolest aspects was the success of the MAC Copilot in final diagnosis of the patient.

My biggest takeaway is that AI in medicine isn’t about replacing clinicians or researchers. It’s about giving them new ways to learn, new perspectives on data, and new tools to guide patient care. Instead of competing with clinical expertise, AI works in tandem with it.

Recently, I had the opportunity to present this work at the ALBA Lab meeting and at the RISE Summer Internship presentation. Here is the preliminary presentation from the RISE presentation.

Code Implementation

PPA CLIP Example Code: Multimodal PPA Predictor.ipynb

Citations

Dubois, S., Romano, N., Kale, D. C., Shah, N., & Jung, K. (2017). Effective representations of clinical notes. arXiv preprint arXiv:1705.07025.

Gorno-Tempini, M. L., Brambati, S. M., Ginex, V., Ogar, J., Dronkers, N. F., Marcone, A., Perani, D., Garibotto, V., Cappa, S. F., & Miller, B. L. (2008). The logopenic/phonological variant of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology, 71(16), 1227–1234. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000320506.79811.da

Gorno-Tempini, M. L., Hillis, A. E., Weintraub, S., Kertesz, A., Mendez, M., Cappa, S. F., Ogar, J. M., Rohrer, J. D., Black, S., Boeve, B. F., Manes, F., Dronkers, N. F., Vandenberghe, R., Rascovsky, K., Patterson, K., Miller, B. L., Knopman, D. S., Hodges, J. R., Mesulam, M. M., & Grossman, M. (2011). Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology, 76(11), 1006–1014. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821103e6

Harris, J. M., Gall, C., Thompson, J. C., Richardson, A. M., Neary, D., du Plessis, D., Pal, P., Mann, D. M., Snowden, J. S., & Jones, M. (2013). Classification and pathology of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology, 81(21), 1832–1839. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000436070.28137.7b

Koleck, T. A., Tatonetti, N. P., Bakken, S., Mitha, S., Henderson, M. M., George, M., Miaskowski, C., Smaldone, A., & Topaz, M. (2021). Identifying symptom information in clinical notes using natural language processing. Nursing Research, 70(3), 173–183. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNR.0000000000000488

Lho, S. K., Park, S. C., Lee, H., Oh, D. Y., Kim, H., Jang, S., Jung, H. Y., Yoo, S. Y., Park, S. M., & Lee, J. Y. (2025). Large language models and text embeddings for detecting depression and suicide in patient narratives. JAMA Network Open, 8(5), e2511922. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.11922

Mesulam, M. M., Rogalski, E. J., Wieneke, C., Hurley, R. S., Geula, C., Bigio, E. H., Thompson, C. K., & Weintraub, S. (2014). Primary progressive aphasia and the evolving neurology of the language network. Nature Reviews Neurology, 10(10), 554–569. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2014.159

OpenAI. (2024, January 25). New embedding models and API updates. https://openai.com/index/new-embedding-models-and-api-updates/

Ortiz, G. G., González-Usigli, H., Nava-Escobar, E. R., Ramírez-Jirano, J., Mireles-Ramírez, M. A., Orozco-Barajas, M., Becerra-Solano, L. E., & Sánchez-González, V. J. (2025). Primary progressive aphasias: Diagnosis and treatment. Brain Sciences, 15(3), 245. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15030245

Radford, A., Sutskever, I., Kim, J. W., Krueger, G., & Agarwal, S. (2021, January 5). CLIP: Connecting text and images. OpenAI. https://openai.com/index/clip/

Roytman, M., Chiang, G. C., Gordon, M. L., & Franceschi, A. M. (2022). Multimodality imaging in primary progressive aphasia. AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology, 43(9), 1230–1243. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A7613

Tak, D., Garomsa, B. A., Chaunzwa, T. L., Zapaishchykova, A., Climent Pardo, J. C., Ye, Z., Zielke, J., Ravipati, Y., Vajapeyam, S., Mahootiha, M., Smith, C., Familiar, A. M., Liu, K. X., Prabhu, S., Bandopadhayay, P., Nabavizadeh, A., Mueller, S., Aerts, H. J., Huang, R. Y., Poussaint, T. Y., … Kann, B. H. (2024). A foundation model for generalized brain MRI analysis. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.12.02.24317992

Warner, E., Lee, J., Hsu, W., et al. (2024). Multimodal machine learning in image-based and clinical biomedicine: Survey and prospects. International Journal of Computer Vision, 132, 3753–3769. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11263-024-02032-8